- Home

- Aaron Allston

Rebel Dream: Enemy Lines I Page 24

Rebel Dream: Enemy Lines I Read online

Page 24

He turned away. Pain shot through him as though a metal spike had been hammered through both his temples with a single blow. He staggered and had to put a hand on the floor to keep from falling over.

But the pain didn’t kill him. He strained against it, rose, made it as far as the door. He had to lean for long moments against the doorjamb to give himself strength enough to continue. Then he could open the door and leave.

As he walked, his steps made unrhythmic by the hammering within his skull, he reminded himself that he was taking data to his controller. He was succeeding in his primary mission. And the pain diminished.

But only a little.

As soon as the door slid shut behind Tam, Danni raised her head to stare after him.

She typed a command into her keyboard. The screen before her changed views to follow Tam as he staggered away down the corridor.

When he was well out of earshot, she keyed her comlink. “He’s gone,” she whispered. “He was either memorizing or recording everything on our screens.”

Iella’s voice came back, not a whisper, but the comlink’s volume was dialed down low. “Did he leave anything?”

“I don’t know. I’ll begin analyzing the recordings now. Out.”

“Good work. Out.”

Danni brought up the first of the recordings made by the holocams positioned at hidden points around the room. She felt her shoulders twitch. She wasn’t sure what Tam had been up to in the long minutes he stood directly behind her, and was desperate to be sure that he hadn’t spread Yuuzhan Vong creatures throughout this office.

Yuuzhan Vong Warldship, Coruscant Orbit

In the operations chamber, surrounded by analysts and advisers, blaze bug displays and recording creatures, banks of villips and standing rows of guards, Tsavong Lah sat at the center of things and listened to reports.

Most of them came from Maal Lah and Viqi Shesh. As they spoke, Tsavong Lah reflected that some things never changed. Normally, it would be Nom Anor and Vergere standing before him, interpreting, offering advice, sniping at one another, one of them a Yuuzhan Vong warrior and the other a clever female of a lesser species. Now, with Nom Anor and Vergere performing other tasks, their roles were still being acted out by others.

“It is a superweapon,” Maal Lah said, using the Basic word rather than the Yuuzhan Vong equivalent. “They have a history of creating devices that can travel faster than light and smash entire worlds, and this is a new one.”

“It’s Danni Quee’s doing,” Viqi said. “It has to be. She’s the only one who could integrate Yuuzhan Vong and New Republic technology this way. I’m going to make that idiot Tam suffer for not killing her when he had the chance.”

Tsavong Lah raised a finger. Viqi bit back on further ranting words. “I just heard heresy,” Tsavong Lah said. “First, the works of the Yuuzhan Vong are not technology. They must never be referred to as such.”

Apparently stricken, though Tsavong Lah suspected it was merely acting, Viqi bowed her head. “I am sorry, Warmaster. I don’t know a word to encompass both disciplines.”

“Perhaps, during your punishment, you will find one. Second, our works could not be melded with infidel technology. The gods would never allow it.”

Viqi and Maal Lah exchanged glances, and it was Maal Lah who dared to correct the warmaster. “This turns out not to be correct. It has already been done. We know that, some time ago, Anakin Solo reconstructed his lightsaber with a lambent crystal … and it appears that he passed knowledge of this technique to others before he was killed. It is also with a lambent crystal that this new device is concerned.”

“Go on.”

Maal Lah gestured to Viqi. She turned to activate the recording creatures on the table behind her. Each, in turn, began to shine, the light above it showing one of the images Tam Elgrin had recorded.

Maal Lah pointed to the image that had been on Danni’s screen. “That is a lambent crystal. Rather, it is a diagram of one. According to the information Viqi’s agent seized, it is being artificially grown in a laboratory in the depths of their garrison building. According to other information we read in these images, they tried to grow the crystals on their ships, but they grow only in true gravity, or dovin basal gravity—their infidel technology gravity ruins them.”

Tsavong Lah offered Maal Lah an expression of revulsion. “So their Jeedai will have more lightsabers? We will not allow it.”

“It is worse than that, Warmaster. The diagram you see represents a lambent crystal as tall as one of our warriors.”

“As tall as … what sort of obscenity could they produce with such a …” And then Tsavong Lah knew what they were producing. He found himself standing, shaking in anger, and did not remember rising. “Bring me my father’s villip,” he said.

In moments, he stared into the villip’s blurry but recognizable simulation of his father’s features. With impatience, Tsavong Lah rushed through the customary greetings. Then he got to the subject of his communication: “I now know what their Starlancer project is. It is another accursed superweapon. The coherent light these vehicles project to one another will at some point be focused through a giant lambent crystal being fabricated in the depths of their building. When this happens, the beam will be of sufficient power to destroy a worldship. The attack we suffered not long ago was a test-firing, perhaps to attune the weapon’s beam to the target.”

“Interesting,” his father said.

“We cannot allow them to perfect this device,” the warmaster continued. “So I now direct you to commit yourself to an all-out assault on that facility and destroy it. Immediately.”

Czulkang Lah was silent for long moments. The villip representing his face froze into such immobility that Tsavong Lah wondered if it had suffered some sort of failure. Then his father spoke again. “To do so would be a strategic mistake,” Czulkang Lah said. “We have not yet gauged our enemy’s tactics or resources. His repertoire of surprises is not fully known. At best, our losses will probably be inappropriately high. At worst, with such a premature attack, we could sacrifice large numbers of warriors needlessly … and still lose. It is too early, my son.”

“My orders stand,” Tsavong Lah said.

His father’s features assumed an expression that all but said, I expected better of you. It was an expression Czulkang Lah wore whenever a student had failed him for the last time. It had never before been directed at Tsavong Lah, and the warmaster took an involuntary step back.

But Czulkang Lah said nothing aloud, no words that would shame his son. Instead, he said, “It will be done.”

“May the gods smile upon your actions,” Tsavong Lah said. He gestured at one of his officers, who stroked the villip. It inverted.

The warmaster stood, his breathing heavy. His father’s final disapproval, so implacable, was like a physical blow to him.

When he was under control again, he turned to Maal Lah. “Issue this directive. When Borleias falls to us, it will no longer be the home of the Kraal. Instead, it will be given to the priests of Yun-Yammka, a haven for their order, in thanks to the god for the gains he has brought us.”

Maal Lah nodded. He, too, said, “It will be done.”

That, the warmaster thought, should send the priests of Yun-Yuuzhan into a fit, and if there truly are conspirators within their orders and the shapers are against me, I will soon know it. He glanced down at his left arm. I will soon feel it.

Borleias Occupation, Day 48

“It has all the characteristics of a major push,” Tycho said.

He, Wedge, and Iella stood before the control chamber’s hologram display. It showed the compiled readouts from all the garrison’s ground-based sensors, including the gravitic sensors Luke’s Jedi had planted in the jungle beyond the kill zone, and incorporated live feeds from starfighters out on patrol.

At the center of the display was the large friendly signal marked “Base.” Out at a distance of a few hundred kilometers, in every direction of the compass, w

ere masses of red blips; Iella counted sixteen separate groups. “What are they doing?” she asked.

“One or two groups are landing personnel, vehicles, everything an invasion force needs,” Wedge said. “The others are distractions. We’re supposed to divide up our attention among them in a desperate attempt to figure out where their landing zone is, and we’re supposed to become nervous because we’re not succeeding.”

“ ‘Supposed to,’ ” Iella said. “Meaning that you’re not? Not doing either one?”

Wedge shook his head. “Oh, we’re sending out scouts to all these sites, but they’re under orders to show up, stay alert, and then make a run for it if anything comes after them. We don’t want to lose pilots acquiring information we essentially don’t need.”

“So you don’t care where their landing zone is?”

“It doesn’t matter.”

“Why?”

“Because, sometime in the next day or two, they’re going to attack us here—and that’s exactly what we want them to do.”

“And when they do,” Iella said, “who are you going to face them with? The New Republic or the Rebel Alliance?”

Wedge and Tycho exchanged a look, and both grinned.

“Neither,” Wedge said. “We’re going to face them with an enemy they’ve never had the displeasure of fighting. We’re going to hit them with the Empire.”

“They’re not going to like the Empire,” Tycho said.

And they told her about Operation Emperor’s Hammer.

Borleias Occupation, Day 48

This time, when the Millennium Falcon arrived on Borleias, it did so in the middle of the night, to no fanfare, no welcoming committee other than a handful of refuelers. Leia saw Han breathe a sigh of thanks, celebrating the absence of ceremony.

Han took Tarc to find him some quarters—the rooms that had been assigned to the underaged Jedi students, where Tarc had previously been staying, would have been reassigned by now, and Han, though he liked the boy, didn’t want him in their own quarters. Leia went in search of her daughter.

Jaina’s X-wing was in the special operations docking bay, a mechanics crew working on it, but Leia could not find her daughter in her quarters or in the former incubation chamber that now served the special operations squadrons—Rogue, Wild Knights, Twin Suns, and Blackmoon—as an informal lounge.

Leia couldn’t call Jaina on her comlink, couldn’t give her the impression that she was keeping tabs, even though that’s what she desperately wanted to do. Eventually, having had no luck in her search, she returned to her own quarters.

And it was there she found Jaina—stretched out on the bed, lying on her side, in her pilot’s jumpsuit, her boots and other accoutrements kicked off to the foot of the bed. Jaina was asleep, and Leia took a moment just to look at her.

Though in engagement after engagement Jaina had been at the controls of one of the New Republic’s deadliest fighter craft, racking up kill after kill against savage enemies, her features were now relaxed in sleep, and she looked as innocent as a child. But she was no child now. She was a young woman, her childhood suddenly, irretrievably gone, and an ache constricted Leia’s heart. We should be away from all this now, she thought. Han and Jaina and Jacen and Anakin and I. And Luke and Mara and little Ben. In a field of flowers. On Alderaan.

Moving slowly and quietly so as not to awaken Jaina, Leia lay down on the bed and put an arm around her. It was a closeness, a protracted closeness that Jaina no longer permitted her in times of wakefulness. Too soon, she heard Jaina’s breathing change as her daughter awakened.

Jaina looked up into Leia’s face and offered a slight, sleepy smile.

“I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to wake you.”

“It’s all right.” Jaina reached up to pull Leia’s arm more tightly around her. “Since you left, I’ve come here sometimes because I knew I could smell you and Dad here. You’d be all around me even when you weren’t here.”

Leia managed to keep an expression of incredulity off her face. Those words seemed so unlike Jaina—so unlike the person she’d become across the last couple of years. “Are you all right?”

Jaina shook her head. “I don’t think so.” She lay her head down on the pillow again. “I don’t think I know who I am anymore.”

“Is it this goddess thing—?”

“No. That doesn’t confuse me in the least. It’s just a confidence game. No, the problem is all being a Jedi, which seems so crystal clear in what you should do and what you should say at any given time … and then being the rest of me, where nothing is clear.” Her expression, what Leia could see of it at this angle, seemed bleak.

Leia chuckled. “Jaina, I’ve been wrestling with the same question since I was only a little older than you are now, and I still don’t have a good answer. Sometimes I’m Jedi and sometimes I’m not. Jedi teaching says that you must turn away from fear. But as a politician, I have to experience fear. Not just my own. The fear of my allies. The fear of my opponents. If I can’t feel it—if I can’t become it, in a sense—I can’t predict which way they’re going to jump when trouble hits. Sometimes being a Jedi just runs completely counter to your other goals. The methodology is just too different.” Softly, she stroked her daughter’s hair, silently willing her daughter’s torments away.

“That’s part of it, too,” Jaina said. “It took me a while to figure it out. I’m afraid.”

“It’s all right to be afraid. You’re surrounded by fearsome things. Being afraid will keep you alive.”

Jaina shook her head. “That’s not it. I’m not afraid of dying. I’m afraid of surviving … and getting to the end of the war and discovering that I’m all alone. That everyone I knew and cared for is gone.”

“Jaina, that won’t happen.”

“It’s already been happening. I mean, it was like having part of me cut off when Anakin died, but with Jacen it’s even worse. As far back as I can recall, no matter what was going on, no matter what was wrong, I could turn around and Jacen would be there. We could be on some distant hideout world or lost in the underbelly of Coruscant or wandering around on parts of Yavin Four no thinking creature has ever seen, and there Jacen was. I never had to be bored, I never had to be afraid, I never had to be alone. When we lost him, I was cut in half. Half of me is gone.” Now the tears came. Jaina wiped them away.

Leia shook her head. “Jacen’s not dead. I know he’s in trouble, but he’s alive. I would have felt him go. I felt it with Anakin.”

The tension in Jaina’s shoulders didn’t ease, but she chose not to argue that point. Instead, she said, “I keep having these thoughts. That I should be planning for the future. Just recently, they’ve gotten, well, even more frequent. But I can’t bear to do that. I can’t plan to have a home on a world when it might not be there tomorrow, or for a career in a service that might be gone, or to spend time with people who keep throwing themselves against the Vong until they stop coming back.”

“I know. That’s what it was like all those years ago, when Palpatine seemed to be an unstoppable force and we were always on the run, and your father was just this ridiculously attractive man who always seemed to be on the verge of leaving us. And do you know what I learned?”

“What?”

“At times like that, you plan for your future by bringing people into your life. You know that they can’t all survive what you’re facing. But those who do, they’re part of your life forever. No matter what, when you fall, they’ll catch you; when you’re hungry, they’ll feed you; when you’re hurting, they’ll heal you. And you’ll do the same for them. And that’s your future. I’ve had whole worlds taken away from me … but not my future.”

Jaina was silent, seemingly thinking about Leia’s words, for long moments. Finally she rolled over onto her back to look into Leia’s eyes. “Actually, I’m glad you got back tonight. Part of why I kept coming here was because I wanted to tell you something. I wanted to let you know that I finally get it.”

“

You get—get what?”

“I had a talk with Mara a few days ago and it really bothered me. It took me until after that really bad furball in space, the one where we almost lost Jag, to figure it out. I finally understood about you sending us, Jacen and Anakin and me, away when we were little. Having to be away all the time even when we were on Coruscant. I’m not stupid, I always knew why. Responsibilities.” Jaina looked off into the distance of time for a moment. “But I never really understood how badly it had to have hurt you.”

“Oh, baby. Of course it hurt. I tried to tell you, time after time. But there aren’t even words for that kind of pain.”

“I know.” Jaina sat up and Leia let her. “I’ve got to go. Reports to write. Goddess stuff to do.” But first she embraced Leia, squeezing her with fierce strength. “I love you, Mom.”

“I love you, Jaina.”

Borleias Occupation, Day 49

Wedge, in Luke’s X-wing, transcribed a lazy arc through vacuum in low planetary orbit. Far below was the near-continuous Borleias jungle. He gave the yoke a hard pull and his course suddenly became a tight circle. He went through 360 degrees of arc, starry sky giving way to jungle outside his canopy, then becoming starfield again, as centrifugal force in excess of the X-wing’s inertial compensator tugged him deeper into the pilot’s couch.

He smiled as he leveled off. “Good to get out once in a while, even when you’re not flying missions, isn’t it?”

R2-D2’s beeps of response came across his comm board. They sounded like an agreement, but not an enthusiastic one.

“Don’t worry, Artoo. Luke will come back. There’s no one in the galaxy who knows how to survive bad places better than Luke Skywalker.”

R2-D2 beeped again, his tones sounding somewhat more encouraged.

Then a voice broke over his comm system, Tycho’s. “General, this is a heads-up.”

Terminator 3--Terminator Hunt

Terminator 3--Terminator Hunt Mercy Kil

Mercy Kil Doc Sidhe

Doc Sidhe Star Wars: Fate of the Jedi: Outcast

Star Wars: Fate of the Jedi: Outcast Fate of the Jedi: Backlash

Fate of the Jedi: Backlash Mercy Kill

Mercy Kill Rebel Stand

Rebel Stand Wraith Squadron

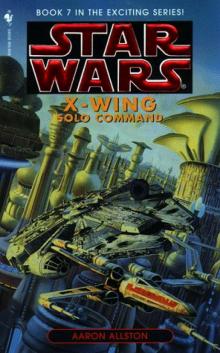

Wraith Squadron Star Wars: X-Wing VII: Solo Command

Star Wars: X-Wing VII: Solo Command Five by Five

Five by Five Solo Command

Solo Command Star Wars: The Clone Wars Short Stories: The League of Spies

Star Wars: The Clone Wars Short Stories: The League of Spies Sidhe-Devil

Sidhe-Devil Star Wars: Legacy of the Force: Fury

Star Wars: Legacy of the Force: Fury Starfighters of Adumar

Starfighters of Adumar Star Wars: X-Wing VI: Iron Fist

Star Wars: X-Wing VI: Iron Fist Star Wars - X-Wing - Iron Fist

Star Wars - X-Wing - Iron Fist Exile

Exile Star Wars: X-Wing V: Wraith Squadron

Star Wars: X-Wing V: Wraith Squadron Star Wars - X-Wing - Starfighters of Adumar

Star Wars - X-Wing - Starfighters of Adumar Rebel Stand: Enemy Lines II

Rebel Stand: Enemy Lines II Rebel Dream: Enemy Lines I

Rebel Dream: Enemy Lines I Outcast

Outcast Star Wars - X-Wing 07 - Solo Command

Star Wars - X-Wing 07 - Solo Command