- Home

- Aaron Allston

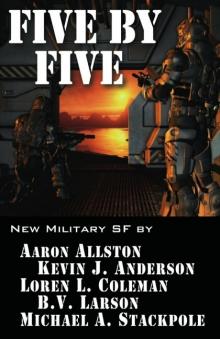

Five by Five

Five by Five Read online

Five by Five

Aaron Allston, Kevin J. Anderson, Loren L. Coleman,

B.V. Larson, Michael A. Stackpole

Big Plush copyright 2012 Aaron Allston

Comrades in Arms copyright 2012 WordFire, Inc.

Shores of the Infinite copyright 2012 Loren L. Coleman

The Black Ship copyright 2012 B.V. Larson

Out There copyright 2012 Michael A. Stackpole

Kobo edition 2012

WordFire Press

www.wordfire.com

eBook ISBN 978-1-61475-049-9

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the express written permission of the copyright holder, except where permitted by law. This novel is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination, or, if real, used fictitiously.

This book is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. Thank you for respecting the hard work of these authors.

Electronic Edition by Baen Books

BIG PLUSH

An “Action Figures” Story

Aaron Allston

–1–

Doc

His booted foot, as long as I am tall, came down on me, grinding me into the black earth. All the air went out of me.

My body held together, though. It was made of hardier stuff than human skin and bone. I didn’t black out.

The giant’s boot covered me from my neck to below my feet, but my head was exposed and I could look up at him. One standard-issue human male, mid-twenties, dressed in camouflage uniform and green-black body armor, glaring down at me, forest canopy over his head.

He had no rifle, but reached for his hip holster.

I knew what was coming. He’d raise his foot and, before I could pry myself from the soil, he’d shoot me. I’d be as dead as my co-conspirators intended me to be.

It was not the way I wanted to spend my day.

* * *

I probably ought to turn the calendar back to explain how me getting stepped on came about.

Picture a living room, sort of triangular. The longest section of sky-blue wall, decorated with imbedded lighting and flexmonitors showing images of Chiron’s forests, oceans, and mountains, is slightly curved because the other side of it is the exterior of a three-story, old-style habitat dome. The other two walls meet at a right angle. There’s white carpet on the floor, the expensive self-cleaning kind, and comfortable puffy furniture everywhere. That’s where I was five weeks before I got stepped on.

For an hour I’d been watching another giant, his head as tall as my whole body, as he napped on his recliner. I sat on the chair arm and waited for him to wake up. I didn’t think he was going to die that day, but you never know what a sudden start might do to someone so old, so I didn’t wake him.

His name was Dr. Bowen Chiang—Doc to me and most people who knew him. At this point he was about two hundred years old, and looking it. His white hair was so sparse it was almost gone and his skin was thin and translucent. He was skinny like so many old humans. He always wore pajamas those days because he was wealthy and eccentric and retired. The ones he had on now were jade-green silk.

I looked like him, too. Not the way he was then, but the way he’d been when he was thirty, when he first left on his emigration to Chiron. I had the tint to my skin and slant to my eyes that used to say “Chinese” to people who worried about that sort of thing, and my hair was thick and black, worn short. Of average height and build for a ’ganger male, I was, by human standards, handsome, with a face that Doc said belonged on the young bad-guy lieutenant in a martial-arts immersive. Doc told me these looks had served him well when he’d lived in a place called Singapore, designing house-cleaning robots and chasing women, before he got married.

You’ve probably never heard of Doc Chiang by that name, but you know him by another. When Chiron was finally terraformed, opening for colonists, he was on the first colony ship headed this way from Earth. His passage came at a reduced rate because he served as a programmer and systems maintenance engineer during the transit. And during those twenty long years, he never went into coldsleep.

Instead, he invented. By the time they made orbit above Chiron, he’d developed the first-generation Dollgangers.

There’s been a lot of misinformation circulated about ’gangers. Let me set matters straight.

Start with a human-like skeleton made of sturdy metal composites. It stands anywhere from 175 to 250 mm tall. (I’m 225 mm, about average for an adult male.) Inside the skull, bones, and ribcage is machinery—a computer system, a plant producing nanite crawlers that diagnose and repair damage, reservoirs of materials for the nanites to use, communications gear ranging from broadband radio to microwave transmitters to laser, extensible microwires for direct data upload/download, voice synthesizer, sensors where the corresponding human organs would be, battery arrays…

Over all that is a musculature of hard-wearing memory polymers attached at innumerable points to the skeleton, and over that a realistic-feeling skin laced with a sophisticated neural net allowing for sensations like pain and pleasure. Throughout the whole body runs a peristalsis-based circulatory system that sends the nanites wherever they need to go.

And that’s only the start. The skin, the facial features, are shaped to individual appearances, making each of us distinctive. We get realistic hair that, supplied and reinforced by the nanites, can grow. Realistic human eyes and skin colors. Fingernails and toenails. Functional genitalia—’gangers are anatomically correct.

But what made us a financial success and first made Chiron a profit-generating world was Doc Chiang’s last innovation before the suits took control of the technology. That innovation was the personality template.

Dollganger programming starts with an unbelievably complex personality system derived from a real human. It might be calculated from a lengthy series of tests or reconstructed from analyses of archival recordings and guesswork. Then, add learning capacity, abstract reasoning, subconscious motivations, complex emotions. The coding is so complex it has to be designed in large part by other machines, and it’s so intricate that it can’t be overridden just by introducing patches of new code.

Though we’re individuals, we have a lot of personality traits in common—cheerfulness, helpfulness, obedience. At least when we’re young.

So the success of the Dollgangers was because each little guy or gal could be made in the likeness of someone specific—of the buyer, of a famous performer, of a planet’s most glamorous model, of an unobtainable object of desire, of a long-dead son or daughter. Oh, yeah, and because we cost a fortune and some people would mortgage their whole futures just to have one of us.

There was just about no task we weren’t put to. Quality assurance on assembly lines making expensive components. Entertainments. Exploration, whether cave strata or new wormhole routes—put us in a miniature spacecraft with a Q-drive and no life support and we’d navigate wormholes too small for human ships and come back with star maps crucial to space exploitation corporations.

And then there was the sex trade. I don’t know the name of the bastard genius who invented the “gang-bangers,” or Dollganger remotes. They weren’t really ’gangers. They looked like us, but they were just sensor platforms, mindless, linked wirelessly to full-immersion

body suits and helmets worn by meat people. A human could put on one of those rigs and link up with a gang-banger. Then everything that the remote experienced was felt by its human operator. Gang-bangers did a lot of things, but mostly they had sex with ’gangers. You want a night with supermodel Sasu of Earth or Derek Ayala, Sexiest Man on Arkon? Well, you couldn’t get the real ones, but you could rent a gang-banger and some time with the ’ganger replica of one of those celebrities.

Which was fine in the early days. We were made to serve, to please. And we couldn’t say no anyway. We were property. But over the years, the fact that all the emotional fulfillment was in one direction only began to make a difference.

And that’s what the meat people never really grasped. Technically, yes, we were robots. But the War of Independence didn’t come about because we were infected with bad code, as governments and news media always imply. It came about because we’re living, feeling creatures.

Anyway, Doc. That’s what Doc invented. He was the Dollmaker of Chiron, and it’s by that nickname most everybody remembers him.

And here I was, perched on his chair arm, watching him sleep, watching him die.

Finally Doc’s breathing changed. His eyes opened. He glanced over at me and smiled. He fumbled for his wire-rimmed glasses and put them on. “Bow. It’s good to see you up and around.” Unlike mine, his voice still carried traces of a Cantonese accent; he’d learned English and other languages well after reaching adolescence.

I cranked my volume levels so he could hear me speak. “Yeah, about that. My system clock and my mental processes clock are offset by nearly twelve hours. There’s a big gap between my last memory and when I woke up in my charger-bed. Something happened to me.”

He nodded, the movement languid. “What do you remember?”

“The Rockrunner shuttle. The heat shields.”

* * *

In those days, Doc lived mostly off his patent royalties, much reduced as patent after patent lapsed. They maintained his home and kept him in essentials, but didn’t allow for luxuries. Luxuries were my department. He rented me out to employers as a hazardous-environment systems maintenance guy, a vehicle specialist, a high-end mechanic. As old and experienced as I was, I earned good money for Doc.

I’d been just about done with one such contract when my memory skip occurred. Rockrunner was a metal hauler that made regular runs out to the system’s metal-rich mining moons. We’d come back with a load and the command crew was getting ready for the return to planetside. But the mission commander saw odd readings on the shuttle’s heat-shield diagnostics.

It was my job to find and fix the problem, of course. In a little full-coverage insulation suit, all crinkly silver, with magnetic boots and a clear bubble helmet, I went extravehicular on the shuttle’s surface to look at the situation.

First I took in the view, of course. Dollgangers do have an aesthetic sense. From high Chiron orbit, I could see the planet of my manufacture dominate the sky. Two-thirds water, the land mass temperate zones full of forests, a hurricane pattern forming in the equatorial portion of the Ephialtes Ocean. The planet was half in daylight, with nighttime at about the midpoint of the continent facing me and racing westward. It was, well, gorgeous.

The damage to the heat shields wasn’t gorgeous, but it also wasn’t too bad. It looked like debris of some sort had scored a couple of forward belly shields. It would take a little work to fix—delaminate the damaged shields, remove them to the shuttle bay, put in a couple of fresh ones, laminate them in place.

I directed a microwave burst toward the cockpit to let the meat crew know the situation. They told me that Punch would assist me with repairs. Five minutes later, he was out there beside me in an identical insulation suit.

I’d known Punch for all my life. He’d been fabbed and awakened a week before I was. Property of Rockrunner’s owner partnership, he was the freighter’s cockpit infielder, capable of acting as comm officer, navigator, or even co-pilot. He had a long, pointed, saturnine face that showed a lot of teeth when he smiled.

He wasn’t smiling today. He was unusually quiet during the repairs. When we were laminating the second of the replacement shields, I bumped helmets with him and held the contact.

I adjusted my vocal tuners to make it easier to hear across the weird medium of plastic bowls. Talking this way, we wouldn’t broadcast. “Let’s hear it, Punch.”

He shook his head. “I’ll tell you when we’re done. I want to talk to you. When it won’t be conspicuous.”

“All r—”

And that’s where my memory ended, right there on that letter “R.”

Eleven hours, thirty-nine minutes, forty-seven point four seconds later, I rebooted, woke up, and found myself in my own charger-bed in Doc’s dome just outside Zhou City, with no idea what had happened.

* * *

I told Doc all this, except the part about Punch wanting to talk to me.

He nodded. “Bow, you got flash-fried yesterday.”

I frowned. Coronal mass ejection, outside a planetary atmosphere, can be pretty dangerous to meat people, but most times it doesn’t do any damage to a Dollganger. When it affects us at all, the damage is usually limited to a reboot. To us, it’s like fainting, then coming to a minute later.

The sympathy on Doc’s face didn’t relent as he continued. “A bad one. The pulse put you down and prevented a normal restart.”

“And Punch?”

He didn’t answer immediately. I had a sinking feeling in my gut.

“They… didn’t find Punch. At best guess, he lost brain functions and his transponder went offline. He probably drifted away from the shuttle.”

“His magnetic boots—”

“He must have kicked himself free of the hull in a muscular spasm. They think his orbit decayed and he went through reentry.”

I sat down. I couldn’t say anything.

Okay, yeah. People praise the programming of the Dollgangers for the way it simulates human emotions. I can tell you, there’s nothing simulated about it, and I was floored.

Punch wasn’t really a close friend. We didn’t pal around on our time off. But he was cheerful, reliable, outspoken, funny.

And now he was dust in the high atmosphere, and I was lucky not to be there beside him.

“I’m sorry, Bow.” Doc’s voice made it clear that he really was. “Look, I don’t need to line up anything for you in the next few days. Take some time off.”

–2–

Lina

In something like a state of shock, I drove my six-wheeled buggy to the west end of Zhou City and beyond.

In the ’ganger lane of the westbound road, just outside the city limits, where landscaped human neighborhoods gave way to dense, two-century-old forest, a dog spotted me and gave chase. It was a good-sized animal, a floppy-eared tan hound.

Dogs seldom mess with ’gangers, but when they do, they can inflict a lot of damage. This one seemed content to chase, wag, and bark, but it was fast enough to gain on my buggy. So before it got too close I hit a dashboard control. This caused a cloud of lemon-scented stink to jet out of the buggy’s rear end. The dog ran into it, then ran off, offended but unhurt.

I turned off the human highway and onto the dirt road leading to Atlas Hill. My buggy’s motor strained as I took the road up to the top. At the hill’s summit, the road leveled off and entered the broad dirt lot surrounding the squat gray building that was the entrance to the Warrens.

I parked as close to the entrance as spaces allowed; there were plenty of other ’ganger transports, especially buggies, parked already. Then I wandered through the vast, human-scale doorway in front and to the first of the ramps leading down.

Meat people had their own ideas about what life should be like for Dollgangers. In their vision, on the downtime hours we needed for recharging, maintenance, and (they eventually discovered) socializing and creative expression, we’d go to the dorms set up for us by our corporate owners or the ’ganger-houses bought

for us by individual owners. I had one of those dwellings, a Dollganger-scaled dome that was a miniature replica of Doc’s house; it occupied a small ground-floor back room in his dome. Dorms and dollhouses were the only structures built for us.

But ’gangers, like meat people, have a need to spend time in environments of our own making. So we built the Warrens.

It had been one of the habitats built for human bioengineers during the transitional years when Chiron was undergoing the last stages of terraforming. They’d used explosives, cutters, and tunnelers to carve burrows throughout a hard rock hill. They’d lived in its tunnels and squared-off caves for years, then had stripped out most of the equipment and abandoned the site the instant the Harringen Corporation began landing prefabs in what was to become Zhou City. A century ago, ’gangers found the place and begun building their own environment inside.

There were apartment blocks and individual homes, some of them with close-cropped lichen lawns. You could find works of art—murals on the walls, sculptures, motorized mobiles, lightshows in constant motion in black-walled chambers. There were businesses: bars and restaurants, dance halls, ball fields, theaters, repair shops.

Twenty-story skyscrapers engineered from resin-saturated cardboard over foam-steel scrap skeletons dominated the main atrium. A stadium occupied what had once been a gymnasium. Housing sprawled through the innumerable former laboratories and dorms. Buildings made from scrap sometimes collapsed or their inhabitants, tiring of unlovely angles and sagging floors, would dismantle them and replace them with something new. It was a one-eighth scale city undergoing constant renovation.

I once had a home in the Warrens, but it kept being dismantled or burned out whenever I was away, so I gave it up. Dollgangers of my sort, the ones who get on really well with their owners and got special privileges—plushes, we were called—weren’t too popular with those who didn’t, and there were places in the Warrens where I just didn’t go. Even now, as I walked, distracted, down Royal Road between the open-air Top Shelf Club, which had once been a set of heavy-duty warehouse shelves, and the monolithic black Simulator Palace, I heard Bluetop, a Zhou City waterworks engineer, call out, “Hey, Big Plush, kissed any new asses lately?”

Terminator 3--Terminator Hunt

Terminator 3--Terminator Hunt Mercy Kil

Mercy Kil Doc Sidhe

Doc Sidhe Star Wars: Fate of the Jedi: Outcast

Star Wars: Fate of the Jedi: Outcast Fate of the Jedi: Backlash

Fate of the Jedi: Backlash Mercy Kill

Mercy Kill Rebel Stand

Rebel Stand Wraith Squadron

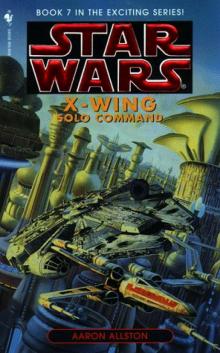

Wraith Squadron Star Wars: X-Wing VII: Solo Command

Star Wars: X-Wing VII: Solo Command Five by Five

Five by Five Solo Command

Solo Command Star Wars: The Clone Wars Short Stories: The League of Spies

Star Wars: The Clone Wars Short Stories: The League of Spies Sidhe-Devil

Sidhe-Devil Star Wars: Legacy of the Force: Fury

Star Wars: Legacy of the Force: Fury Starfighters of Adumar

Starfighters of Adumar Star Wars: X-Wing VI: Iron Fist

Star Wars: X-Wing VI: Iron Fist Star Wars - X-Wing - Iron Fist

Star Wars - X-Wing - Iron Fist Exile

Exile Star Wars: X-Wing V: Wraith Squadron

Star Wars: X-Wing V: Wraith Squadron Star Wars - X-Wing - Starfighters of Adumar

Star Wars - X-Wing - Starfighters of Adumar Rebel Stand: Enemy Lines II

Rebel Stand: Enemy Lines II Rebel Dream: Enemy Lines I

Rebel Dream: Enemy Lines I Outcast

Outcast Star Wars - X-Wing 07 - Solo Command

Star Wars - X-Wing 07 - Solo Command