- Home

- Aaron Allston

Five by Five Page 20

Five by Five Read online

Page 20

So saying, Kerth aimed and shot the plant nearest to Gersen. The central bole of it was pierced, and it shivered in shock. A moment later, it began to thrash.

Gersen had experienced a field in a panic before, and he wasted no more time. He began to run. His feet brushed leaves now and then, and even stepped upon the rubbery length of a squirming vine.

The first plant realized it was injured and went into a frenzy, causing those around it to respond. Like a spreading ripple on a pond, soon all the plants were whipping about, lashing furiously.

Gersen ran and ran, and behind him the air rang with Kerth’s laughter.

–10–

Not wanting to damage any valuable technology the villagers might possess, the Pilot brought the Black Ship down in the fields between the sea and the walls. The flora under the ship writhed in agony and died, turning into burnt scraps of flapping cellulose. Leaves curled and pods shimmered before bursting into flames. Polyps exploded, gushing out steaming vapor and foul, sticky liquids which were soon vaporized in turn.

“Strange plants here,” muttered the Captain as he pressed his orbs to the scope. “I’m not particularly impressed by their domes. They are at least manufactured, but they look old and decrepit.”

None of the crew dared speak. The Pilot landed the ship with a final jolt. They were down. The ship had been designed for both interstellar and atmospheric travel. Most interstellar vessels were built to stay in space forever, but the mech-based technology of Talos was different. The crew could withstand much higher G-forces, as their bodies were mostly artificial. The equipment required to make spaceflight comfortable for humans was thus unnecessary aboard a Talosian ship. There were no inertial dampeners, cryotanks to freeze bodies, nor even much in the way of life support. Food and oxygen production systems were aboard, but minimal. Mechs only had to feed a few pounds of brain tissue, and consumed little.

Most of the vessel’s mass was dedicated to engines, weapons, and power—very little else was required. The ship was smaller in design and more efficient than human ships. Humans would have found it cramped, freezing cold and almost airless, but none of these conditions bothered mechs.

The unloading ramp rolled down, and the hatch opened. Air was sucked into the ship, which maintained a low pressure during flight due to seepage. Everyone’s orbs were quickly fogged over by humidity as the warm, moist air touched the freezing metal.

The Captain cursed and rubbed at his face ineffectively with his grippers. The effect quickly passed, however. “Deploy the First Tactical Squad,” he roared over the regional net. “Standard formation, weapons active. Destroy any resistance, but take care not to damage equipment.”

Everyone aboard watched the First Tactical Squad as it deployed. The Marines marched smartly down the ramp onto the smoking field. A few of the burnt plants at the base of the ramp quivered with the last of their vitality as they were trod upon, but were unable to resist.

Eight Marines left the ship and headed toward the village gates in a column, two abreast. Each had a burner held diagonally across the chest. The flared tips of the weapons wisped with blue light and shimmering vapors rose up into the sky.

The squad halted when they reached the gates and regarded the primitive defensive structure. The Sergeant stepped forward, examining the hinges and wire-wrapped flap-like doors. He was not impressed.

A snap and a whirring sound alerted the squad. A shower of three sticks struck the chassis of two, and the orb-socket of a third. They examined the sticks briefly. They classified them as primitive projectiles of cellulose, tipped with triangular steel heads.

“We’ve been attacked,” the Sergeant said. “Return fire.”

Without further hesitation, the squad lifted their burners and released a gush of lavender plasma. This plasma was similar to flame, but much hotter and longer ranged. It licked out in a three-foot swirl from the throat of every gun and blew holes in the gates and the watchtower that sat above them.

“Hold your fire, you aren’t even injured,” the Captain transmitted in annoyance. “What if there is something of value in that tower?”

Reluctantly, the Marines lowered their burners. The damage had been done, however, and the old watchtower was now teetering on three girders rather than four. It slid crashing down toward the Marines. They clanked backward, servos whirring as they attempted to avoid damage.

The Captain muttered complaints. “Examine those ruins. Is there any sign of technological equipment? A radio, anything?”

The Sergeant picked among the tumbled stones and tangled scraps of metal. The fortification appeared to be held together with rusty wire. He did find a body, which he pulled from the rubble and held up by one leg. It was a male, dressed in tattered cloth. The Sergeant squeezed too hard with his gripper, and snipped off the man’s leg at the calf. Marine grippers were sharper than those wielded by technicians and command personnel. He dropped the mess, causing a wet slap of dead blood to shower the dusty stones.

“Nothing?” demanded the Captain. “Just a few men with stick-throwing devices? These people are primitives. ENGINEER!”

* * *

The Engineer had been waiting for the Captain to demand his presence. He’d also expected the call to be a long, roaring summons, not a polite request. However, he hadn’t expected the order to come so soon.

He hurried to make his final adjustments to the equipment he’d spent the last day and a half building, and urged his Technicians toward the unwieldy system. It resembled a black metal box with various bulbous extensions and connective polymer tubes. The Technicians advanced dubiously. He gestured for them to hurry, and they gingerly picked up the jumble of equipment, carrying it awkwardly in their grippers.

“Follow me, and don’t lag behind,” the Engineer ordered.

Quickly, the trio mounted the ramps and marched toward the bridge. They met the Captain and two of his Marines coming the other way.

“Ah, there you are at last,” said the Captain. “Would you like to examine the treasure trove of equipment we’ve discovered on this rock? I’m sure you will be amazed. Perhaps we should abandon our current ship, rebuilding a better vessel with the amazing local components. We will fly to our target in luxury!”

The Engineer was unaccustomed to sarcasm, but he understood the other’s meaning clearly enough: he was displeased. The Captain was freer of mind than most of the mechs aboard, who were conditioned to follow an assigned task with little in the way of errant thought processes. The Engineer was similarly unfettered, but his mind was not so free as to have a true sense of humor.

“I would like to see that, yes,” the Engineer said, deciding to feign ignorance.

The Captain growled in frustration. He reached out grippers and clamped them onto the Engineer’s shoulders.

“So would I,” he said. “But there’s nothing like that here. You have misled the expedition. Valuable time has been lost.”

For a moment, the Engineer cogitated. A new possibility occurred to him, one he had not previously considered. Perhaps the Captain had become unbalanced at some point. He did not know why, but the possibility could not be discounted. His commander was not behaving within normal parameters, and although the Captain wasn’t malfunctioning, he wasn’t entirely rational, either.

“I’d like to point out that I did not recommend this course of action,” the Engineer said.

“Ah!” said the Captain, his voice rising almost to a screech. “There it is! I knew it must come eventually. Your very first excuse. I can tolerate almost anything, Engineer. I can withstand ineptitude, treachery, even outright failure—but not excuses.”

“I’ve never demonstrated any of the listed traits.”

The Captain loomed near now, his plastic eyes seeming to bulge. “That’s your second excuse.”

“No, sir,” the Engineer said. “You are in error. The statement of a pertinent fact is a justification, rather than an attempt to shift blame.”

The Captain reached

down with a trembling gripper to his belt and unclipped his disconnection device. He fumbled for the firing stud, as if he could not move fast enough due to his eagerness.

“Perhaps I can aid you with that,” the Engineer said, reaching out a gripper.

The Captain reeled back as if stung. “Back!” he cried. He waved his Marines forward. They shouldered their way between the Captain and the Engineer.

“Your disconnection is long overdue,” the Captain said, aiming his device between the narrow metal waists of the two hulking Marines.

“A pity,” the Engineer said.

The Captain hesitated. “What do you mean?”

“Clearly, you have searched the entire village, found their stashed equipment and plundered it. It is a pity the discovered equipment was not useful.”

The Captain wavered. “Are you still claiming these primitives have advanced components? That they are hiding their true tech? Why would they do that?”

“I could only speculate on their reasons. But I have built something that will allow me to discover the exact location of their most advanced systems.”

So saying, the Engineer turned and tapped a gripper on the metal box his Technicians carried behind him. “That is the purpose of this device I’ve designed. It is very sensitive over a short range. We have only to walk among their domes until we find a strong signal.”

“What if they have buried their equipment? What then?”

“When we find evidence of it, we will persuade them to dig it up.”

“How?”

“As I understand human physiology, the removal of scraps of flesh is unpleasant for them. We will catch humans and trim them until they produce their treasures.”

The Captain laughed and lowered his disconnection device. Everyone present relaxed somewhat, except for the Marines, who were so mission-focused they didn’t seem to be aware of the change in mood.

A few minutes later, the Engineer found himself standing in front of the ramshackle gates. He looked at the village, aghast. The situation was far worse than he’d imagined. These people were more likely to possess a herd of goats than a useful subsystem. But like countless shamans before him, he was trapped. He would just have to bluff it through.

The Marines completely burned down the gates with gouts of purple plasma. They ripped the remaining shreds of metal out of the way, and the party marched into the compound. Last in line were the two Technicians, carrying the Engineer’s strange, metal box.

–11–

Gersen awakened drifting offshore the day after he’d fled the island. He was sprawled aboard his tiny boat. He groaned aloud and hung over the side, vomiting until his sides hurt. The sun was bright and directly overhead giving him a headache to go with everything else. Next, he turned a bleary eye downward to examine his injuries.

He found numerous scrapes and perhaps ten embedded red spines. He plucked these out, and rubbed salve from the boat’s meager stores into the wounds so they would not fester. There were toxins in his system, he was sure of that. But very little venom had been injected. If he had received a large dose, he would never have awakened at all.

When he felt better he sat up in his boat, which rolled on gentle swells. He was less than a mile from the island, and would have drifted farther if he hadn’t dropped anchor.

He nursed his wounds, shivered from his ordeal, and chewed stale rations of dried fish wrapped in salted seaweed. Soft, edible corals sat in a pool of brine in the bottom of the boat. He chewed these tasteless but nourishing growths and studied the shoreline.

He had an experienced eye when it came to pod-walkers. He knew their seasonal activities well. By his estimation, he’d left the island just in time. An army of walkers now roamed the rocky shoreline. Every beach was full of fresh pods dragged up from the sea bottom. They were beginning a new planting, working their way up and down the beach.

The life cycle of the Faustian pod-creatures was a strange one, and only the humans that were native to the planet understood it in its entirety. Like some amphibians of Old Earth, the creatures changed forms as they aged in stages. Like salmon, these stages of life were spent in different environments.

Every pod-creature began its existence as a lumpy growth on the bark of a pod-walker. When these podlings dangled from their parent creature, hanging from feeding tubers, they were ready for independence and were plucked free. The second stage of life began when they were planted upon the seafloor near a sandy beach. When they’d grown to a certain point, usually taking less than a terrestrial year, they were transplanted again by pod-walkers onto dry lands, usually near a coastline.

Once seeded on the shore, they grew more and more mobile and toxic. It was during this initial planting on land that they grew ganglia, began to feel pain, and gained a primitive capacity for movement. They did not have true muscles, nor a true brain. Like the starfish of Earth, they lacked real cognitive abilities, but reacted to stimuli and their physiology was capable of limited motion.

Eventually, when these plants ripened, they were harvested by the same pod-walkers that had planted them and hundreds of pods were all dumped together into deep holes in upland regions. They grew into a tree-like growth in the fourth stage until they finally split open and a pod-walker emerged from the swollen polyps that grew like tumors on every tree trunk. A given tree might produce new pod-walkers for thirty seasons before becoming barren and derelict.

The pod-walkers were the only truly mobile stage of the life cycle. These strange beings marched about, enabling the various other stages of their species’ odd reproductive cycle. The walkers themselves tended to hibernate when not needed by any local podlings. They were influenced by the seasons just as the rest of their brethren were, and came alive and fully animated only when needed by their young.

Gersen pulled up his anchor and made ready to set sail. This island had been a bittersweet experience—mostly bitter. He would gladly leave it behind.

But something made him delay. He sat and watched the pod-walkers roving on the beach. There were a lot of them, all covered in seaweed and splashing with their broad, stumping feet. They walked on a tripod of limbs, each leg possessing a permanently bent knobby knee. Their legs were as thick as tree trunks, and their towering crowns carried between seven and twenty whipping vines. These vines were like small hands on tentacles. They could carry objects such as pods or captive prey. The vines often snapped off, in which case they shriveled and died like old leaves. New ones grew continuously to replace the lost limbs.

No one knew how the pod-walkers had evolved. There were guesses, but the initial colonies had been so devastated by the first animated seasons they’d experienced that there was no botanist left who was qualified to answer these questions. They remained a mystery, and the surviving colonists lived in a delicate truce with them. As long as humans had no contact with the juvenile plants—and more importantly the walkers—no one died. Unfortunately, the pods in their myriad forms were the dominant life form on Faust, and not easily avoided.

Gersen peered past the bustling walkers, looking beyond them to the village, which was hidden by the undulations of the land. It seemed to him that smoke wisped upward from that direction. He frowned. Just what were the villagers doing? What was Kerth up to right now? Had he perhaps staged a coup against the gullible Bolivar? Was Estelle enduring an assault even as Gersen floated on the waves?

He sighed and turned his face away from the island. “Let well enough alone,” his father had told him long years ago. In general, that had always been his creed. He’d drifted through ten villages like this one, although most of them had been less isolated and his visitations less adventurous.

In the end, he did not set sail and head for the mainland as he’d intended. With a growl of frustration, he took up the oars and rowed. He turned his craft around and headed back toward the beach.

In his mind, he considered a score of reasons to take action: he was angry with Kerth; he wanted to see if Estelle was all right

; his pride had been injured; and he sought revenge. All of these were compelling, to one degree or another.

He was angry with himself almost as much as he was with the villagers who had chased him out of the settlement. He supposed it was pride that drove him back into danger, as much as anything else. He’d been freely abused, and he could not let that abuse stand unanswered. He also admitted to a strong desire to experience Estelle’s soft voice and even softer touch again.

When he reached the point where the waves crashed upon the sand around him, he had to dodge the pod-walkers, who were beginning to sense his presence. In a rippling series of splashes, the monsters thumped down each of their three, stump-like feet in the surf with thunderous reports. At first, they trundled past his tiny boat without a care. They were blind, but they had excellent heat-sensing organs. They did not see in the infrared, but they could feel moving sources of warmth that came near them, even as a torch waved near a blindfolded man’s arm would inevitably make him flinch.

Gersen tossed the anchor down when he could touch the bottom with a probing toe, but he didn’t simply make a thrashing run for the beach. Instead, he dove into the water and cooled his body off with the seawater. Sliding along just under the surface, he turned his head up to suck in infrequent breaths.

He soon reached the shoreline. Lying in the surf with waves rolling over him, he attempted to time his next move. It was not easy, as the pod-walkers seemed to be everywhere.

In the end, he hesitated too long. A pod-walker came splashing up behind him from the seabed. It was a big one, with no less than nineteen whipping vines hanging from a gargantuan crown. These vines dragged a load of fresh sea-podlings behind the monster, ready to be planted in the dry sands.

Gersen realized he could not slip away to the right or left down the beach due to the proximity of more walkers. He did the only thing he could: he stood up and ran for the dirt track that led uphill to the village.

Terminator 3--Terminator Hunt

Terminator 3--Terminator Hunt Mercy Kil

Mercy Kil Doc Sidhe

Doc Sidhe Star Wars: Fate of the Jedi: Outcast

Star Wars: Fate of the Jedi: Outcast Fate of the Jedi: Backlash

Fate of the Jedi: Backlash Mercy Kill

Mercy Kill Rebel Stand

Rebel Stand Wraith Squadron

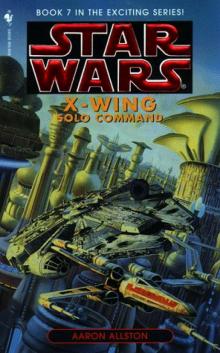

Wraith Squadron Star Wars: X-Wing VII: Solo Command

Star Wars: X-Wing VII: Solo Command Five by Five

Five by Five Solo Command

Solo Command Star Wars: The Clone Wars Short Stories: The League of Spies

Star Wars: The Clone Wars Short Stories: The League of Spies Sidhe-Devil

Sidhe-Devil Star Wars: Legacy of the Force: Fury

Star Wars: Legacy of the Force: Fury Starfighters of Adumar

Starfighters of Adumar Star Wars: X-Wing VI: Iron Fist

Star Wars: X-Wing VI: Iron Fist Star Wars - X-Wing - Iron Fist

Star Wars - X-Wing - Iron Fist Exile

Exile Star Wars: X-Wing V: Wraith Squadron

Star Wars: X-Wing V: Wraith Squadron Star Wars - X-Wing - Starfighters of Adumar

Star Wars - X-Wing - Starfighters of Adumar Rebel Stand: Enemy Lines II

Rebel Stand: Enemy Lines II Rebel Dream: Enemy Lines I

Rebel Dream: Enemy Lines I Outcast

Outcast Star Wars - X-Wing 07 - Solo Command

Star Wars - X-Wing 07 - Solo Command