- Home

- Aaron Allston

Starfighters of Adumar Page 10

Starfighters of Adumar Read online

Page 10

“But circumstance dictates tactics,” ke Mattino said, his voice a protest. “The greatest honor comes from killing the most prestigious enemy.”

“No,” Tycho said. “That’s the second greatest honor. The greatest honor comes from protecting those who are depending on you. Which you can’t do if you get yourself killed.”

Wedge nodded. “The question is, are you earning honor so that your loved ones can be proud of you as they stand over your grave, or so they can be proud of you when you come home at night?” He raised his brewglass to drain it, but was hit by a hollow feeling as his words came back on him: The question was merely an academic one to him. He had no one to come home to. He even had fewer friends than he’d thought, having somehow lost Iella while he wasn’t looking.

To disguise his sudden feeling of disquiet, he went to the bar to get his brewglass refilled, leaving Tycho to continue in charge of the conversation. Two words were still haunting the back of his mind, intruding when he wasn’t absolutely focused on some other subject: Lost Iella.

By the time he got back to the table, the pilots there were on their feet, shaking hands. “Unfortunately,” ke Mattino was saying, “other duties do demand some small portion of our time. Is there a chance you will be accepting challenges again tomorrow?”

“Until our own duties demand all our time, there’s a high likelihood of it,” Wedge said. “In fact, tomorrow, we may bring the X-wings over and show you how we fight at home.”

“That is something I would wish most fervently to see,” ke Mattino said. He saluted, waving his tight fist a few centimeters before his sternum in an odd pattern. It took Wedge a moment to recognize the motion: It was the same as Cheriss’s salute the night of her duel, but without the blastsword in hand. “I hope to see you on the morrow,” the captain said, then turned away, pulling his hip cloak around him in a dramatic flourish.

Today, the people of Cartann had apparently discovered that Wedge and his pilots were flying at the air base. When they and Cheriss departed the base on their rolling transport, the street was thick with admirers. They clustered up against the rails, offering things to Wedge and the pilots—flowers, Adumari daggers, folded notes scented with a variety of exotic perfumes, necklaces, metal miniatures of the Blade-32 fighter-craft, objects too numerous to catalogue. Wedge accepted none of them, preferring instead to shake hands with as many of his admirers as could reach him, and his pilots followed suit.

Their procession slowed to a halt at a major cross avenue, however, blocked by a similar parade—people thronging around an identical wheeled transport returning from Cartann Bladedrome. Aboard, Turr Phennir and his Imperial pilots accepted the gifts and accolades from the crowd. Phennir gave Wedge a mocking smile as his transport rolled serenely past the stalled New Republic entourage.

“What’s his record for today?” Wedge asked.

“He accepted two challenges, and he and his pilots shot down two half flightknives,” Cheriss said. “Experienced pilots, good ones. He gained considerable honor today.”

“Yes, he’s just rolling in the honor coupons,” Wedge said. He didn’t bother to refrain from glaring at Phennir’s retreating parade. “They stick to the blood all over him.” He caught sight of Cheriss’s confused expression and waved the thought away.

Tycho, at Wedge’s ear, murmured, “Phennir has known for a day or two what we just found out today. That Adumari pilots just aren’t very good.”

“A few of them have decent technical skills,” Wedge said. “But not many. The attrition they experience has to be keeping their level of proficiency pretty low. Add that to their lousy tactical choices…”

“Small wonder they treat us like supermen,” Tycho said. “Us, and that happy band of Imperial murderers over there.”

In the days to come, Wedge’s routine requests for an audience with the perator to discuss diplomatic relations were met with routine refusals and apologies. But Tomer reported that rumor had it that the perator and his ministers were drawing up a proposal for the formation of a world government—a move, Tomer gleefully announced, that benefited the New Republic more than the Empire and therefore had to be interpreted as a slight gain for their side. Wedge, unconvinced, didn’t bother to point out that the Empire would find it easier to rule this world through an existing planetary government.

Each day, Wedge and Red Flight would return to the air base and conduct training exercises with Adumari pilots. Usually Red Flight used Blades, but sometimes they flew their own X-wings, to the astonishment of the Adumari, who were impressed with and appalled by the smaller crafts’ greater speed, maneuverability, and killpower.

In the first couple of days, the challenger pilots were all from Cartann, but soon afterward flightknives began visiting from distant nations with exotic names like Halbegardia, Yedagon, and Thozzelling. In spite of the contempt with which Cartann pilots treated these newcomers, Wedge made sure that Red Flight’s attention was divided equally among all pilots who showed an interest.

Each day, the kill numbers of General Turr Phennir and his 181st Fighter Group pilots climbed. According to Cheriss, Phennir’s popularity also rose above that of Wedge and the New Republic flyers. “The Imperial pilots,” she said, “show more affection for Cartann by doing things the Cartann way; how can the people of Cartann not respond with more affection?”

“By remembering the sons and daughters they’ve lost?” Wedge suggested.

The pilots’ nightly activities usually involved accepting dinner invitations made by prominent politicians and pilots of Cartann. Sometimes these affairs were simple dinners, sometimes lavish spectacles of entertainment, sometimes storytelling competitions among the survivors of aerial campaigns.

Wedge almost never saw Turr Phennir and the Imperial pilots at these dinners. Most were small affairs, orchestrated so that the host could showcase the pilots for a choice number of guests, and even at the larger affairs there seemed to be a growing division among Cartann nobles—on one side, those who preferred the New Republic; on the other, those who preferred the Imperials. Increasingly, the more prestigious nobles seemed to extend their invitations to Turr Phennir rather than Wedge Antilles.

Red Flight and Cheriss spent one afternoon visiting a facility Wedge hoped would one day serve the New Republic. Buried hundreds of feet below the city of Cartann, it was a missile manufacturing plant.

The Challabae Admits-No-Equal Aerial Eruptive Manufacturing Concern was a succession of enormous rectangular chambers separated by tunnels. Portions of the ceiling above each chamber were open to an upper tunnel series, and it was from catwalks along these upper tunnels that the pilots observed the details of the manufacturing process.

Chambers early in the sequence took in raw materials, including metals, man-made materials, and raw chemicals, and began processing them into components such as missile bodies, circuit board frames, wiring, explosives, and fuels. Chambers farther along would test missile body integrity, define and test the functions of circuitry, and test explosives and fuels for purity and reliability. Toward the end of the kilometers-long facility, chambers were used for final assembly and quality checking of finished missiles.

But though each chamber would have a different function from the ones nearest it, all chambers shared characteristics in common. There was a grimness to them all that lowered Wedge’s spirits.

Each chamber was filled with assembly lines, conveyor belts, and other machinery, all painted in the same lifeless tan-brown. Each chamber was occupied by hundreds, sometimes thousands, of workers, men and women, all of whom wore featureless garments in a darker brown. Walls were an eye-deadening off-white; floors were a dirt-colored brown. In chambers where manufacturing processes released smoke or soot, even the air was brown. Regardless of the air color, it was always sweltering.

Wedge saw workers moving and laboring. He saw none smiling. None looked up to see him or his companions on the catwalk far above.

“Where do they all live?” he asked

. “I can’t remember seeing masses of people wearing workers’ garments like those. Not anywhere.”

Berandis, the plant’s assistant manager in charge of public concerns, a lean man whose mustache was topped by a series of ridiculous curls held in place by some sort of wax, gave him an easy smile. “Well, they live wherever they want and can afford, of course. Most are in turumme-warrens, above.”

“I’m not sure I understand.”

Cheriss said, “Turummes are reptiles, distant relatives of the farummes you’ve seen. They dig elaborate nests in the ground. So large banks of apartment quarters built below the surface are often called turumme-warrens. The warrens above a plant like this are always owned by the plant.”

“Some workers live aboveground, of course,” Berandis said. “There are no laws to keep them in the warrens. But few can afford aboveground housing. Mostly you see it with managers, stewards—”

“Informants,” Cheriss said. “The occasional parasite.”

Berandis’s smile did not waver, but he lowered the tone of his voice. “Manufacturing plants are the same all over Cartann,” he said. “But we do offer a difference. Our missiles are the best, which is why we are the recipient of the government contract for all missiles for Cartann’s Blade-Thirties and Blade-Thirty-twos. A pilot like you can stake your life on a Challabae missile and know that it will serve your purpose faithfully and reliably. This gives our workers something to be proud of.”

Hobbie nodded. “I can tell. You can see the pride on their faces.”

Berandis beamed, oblivious to sarcasm.

On the long walk back to their start point, Cheriss dropped back behind Berandis to march with the pilots. Her voice artificially cheery, she said, “There is another advantage to having worker quarters above plant facilities of course.”

“Which is what?” Wedge asked.

“Well, if some enemy were to fill the skies above Cartann City and drop Broadcap bombs on the plant, the bombs would only penetrate as far as the warrens before exploding. The plant would take little or no damage.” Her tone was light, but Wedge detected something in it—bitterness or sarcasm, or perhaps both. He couldn’t tell.

Tycho said, “You’ve either worked at a plant like this or lived in the turumme-warrens, haven’t you?”

“Both,” she said. “My mother worked at a food-processing plant until brownlung killed her. I worked there for a season before I was well established enough to make my living with my blastsword.”

“How, precisely, do you make your living?” Wedge asked. “By taking trophies from the enemies you defeat?”

“No… though I did that at first. Now I use only blastswords manufactured by Ghephaenne Deeper-Craters Weaponmakers, and they pay me regularly so that they can mention that fact in their flatscreen boasting.”

“Endorsements,” Hobbie said. “I could do that instead of flying. I’ve had offers from bacta makers. Bacta’s a sort of medicine,” he added for Cheriss’s benefit.

She offered a little frown. “You are not a well man?”

“I’m well enough. But the ground and I get along so well we sometimes get together a little too vigorously.”

“So let me be sure I understand this,” Wedge said. “Under Cartann City, there are lots of underground manufacturing concerns, huge ones, where they make missiles and preserved food and Blades and everything Cartann needs, with worker quarters—where most workers have to live because they can’t afford anything else—above them but still underground.”

Cheriss nodded.

“And we don’t see these workers aboveground because?”

“Because they’re too tired at the end of a long day of working to do much but eat and watch the day’s flatscreen broadcasts,” Cheriss said.

“How much of the population lives belowground, compared to what we’ve seen aboveground?”

“I don’t know.” She shrugged. “Forty percent, perhaps. But don’t feel that they are trapped, General Antilles. They can always break free of the worker’s existence. They can volunteer for the armed forces. They can take up the life of the free blade, as I’ve done.”

“So the only sure way for them to get out is to risk their lives.”

She nodded.

Wedge exchanged looks with the other pilots, and his appreciation for the world of Adumar dropped another notch.

Later the same day, Tomer Darpen visited the pilots’ quarters with some bad news. After two days of incarceration, the surviving four men of the six who’d tried to assassinate them had escaped. “Definitely with the aid of someone in the Cartann Ministry of Justice,” Tomer said. “Whoever paid them in the first place had enough money or pull to enlist the aid of a whole chain of conspirators.”

“They’ll be coming after us again,” Hobbie said, a mournful note in his voice.

Cheriss shook her head. “They were not just defeated but embarrassed last time. They’ll be instructed to come after you again to regain their honor. But instead they’ll probably run. And so they’ll either vanish from the face of Adumar… or be found dead in an alley, a warning to others who might contemplate failure.”

Still, Wedge was not entirely displeased with the way things were shaping up. His informal flying school at Giltella Air Base was actually proving to be a satisfying experience. Increasingly, pilots both from Cartann and foreign nations were discussing Wedge’s philosophies as much as his tactics and skills, and doing so without contempt. One Cartann pilot, barely out of his teen years, a black-haired youth named Balass ke Rassa, finally summed it up in a way that pleased Wedge: “If I understand, General, you are saying that a pilot’s honor is internal. Between him and his conscience. Not external, for his peers to see.”

“That’s right,” Wedge said. “That’s it exactly.”

“But if you do not externalize it, you cut yourself off from your nation,” Balass said. “When you do wrong, your peers cannot bring you back in line by stripping away your honor, allowing you to regain it when you resume proper behavior.”

“True,” Wedge said. “But by the same token, a group of people you respect, even though they don’t deserve it, can’t redefine honor for their own benefit, or to achieve some private agenda, and then use it to control your actions.”

Troubled, the youth withdrew from the post-duel conversation and sat alone, considering Wedge’s words, and Wedge felt that he had at last achieved a dueling victory.

Chapter Six

The night of the discussion with Balass ke Rassa was one of the few in which the pilots had declined all dinner invitations, giving them a chance to dine in their quarters and get away from the pressure of being on display before the people of Cartann.

As the ascender brought them up to their floor, Janson said, “They’re calling me ‘the darling one.’”

“Who is?” Wedge asked.

“The court, the crowds. They have tags for us all now, and I’m the darling one. Tycho is ‘the doleful one.’”

Tycho frowned. “I’m not sad.”

“No, but you look sad. Makes the ladies of Cartann’s court want to comfort you. They’re so sad about wanting to comfort you that you could comfort them.”

Hobbie snorted. “And Tycho the only one of us with a successful relationship with a woman. Missed opportunities, Tycho.”

They paused before the door to give its security flatcams—primitive devices by New Republic standards, but still capable of facial recognition—time to analyze their features. Janson continued, “Hobbie is ‘the dour one.’ Not too much romance in that, Hobbie. And Wedge is ‘the diligent one.’ That may not sound too romantic, Wedge, but ‘diligent’ has a couple of colloquial meanings here that add to your luster—”

“I don’t want to know,” Wedge said. The doors opened. “Say, look who’s here.”

Hallis sat on the monstrously overinflated chair situated in one corner, her legs up over one of the chair arms. She waved. Her recording unit, Whitecap, said, “Say, look who’s here” in inim

itable 3PO unit tones.

Wedge led his pilots in. “What’s with Whitecap?” he asked.

“What’s with Whitecap?” Whitecap asked.

Hallis made a cross face. “Oh, something’s gone wrong in his hardware.”

“Oh, something’s gone…”

“I was recording some of General Phennir’s challenge matches out at the Cartann Bladedrome. When the pilots were leaving, the crowd got a bit unruly and I was knocked down. Since then, Whitecap repeats back everything anyone says within earshot. I can’t get him to stop.”

“…get him to stop.”

Janson grinned at her. “Some days make you just want to beat your heads against a wall, don’t they?”

Hobbie said, “Maybe not. The young lady might not have her heads on straight, after all.”

Tycho said, “Still, I think she ought to get her heads examined.”

Wedge looked at them, appalled.

“Pilots,” Hallis said. “How did I ever get this assignment? Who did I offend?”

“…did I offend?”

“Still,” she said, “you’d better be nice to me. I know you don’t take me seriously, but you ought to.” Her expression was unusually earnest.

“…you ought to.”

Wedge sprawled on a sofalike piece of furniture large enough to accommodate three full-sized people comfortably. “Hallis, it would be easier if you didn’t look like something out of a tale to frighten children.”

“…to frighten children.”

“All right,” she said.

“All right.”

She pulled her goggles off and set them aside. Then she reached up to press a control on Whitecap’s clamp; with a hissing noise, it relaxed and the recording unit began tilting from her shoulder. She caught it as it pitched forward, then moved across the room to set it within a cabinet. She closed the cabinet door with an irritated thump; from inside, Whitecap did a credible job of imitating the noise. “Better?”

Wedge tried to make his tone neutral, nonjudgmental. “What is it, Hallis?”

Terminator 3--Terminator Hunt

Terminator 3--Terminator Hunt Mercy Kil

Mercy Kil Doc Sidhe

Doc Sidhe Star Wars: Fate of the Jedi: Outcast

Star Wars: Fate of the Jedi: Outcast Fate of the Jedi: Backlash

Fate of the Jedi: Backlash Mercy Kill

Mercy Kill Rebel Stand

Rebel Stand Wraith Squadron

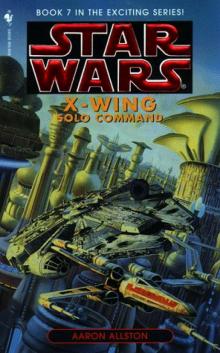

Wraith Squadron Star Wars: X-Wing VII: Solo Command

Star Wars: X-Wing VII: Solo Command Five by Five

Five by Five Solo Command

Solo Command Star Wars: The Clone Wars Short Stories: The League of Spies

Star Wars: The Clone Wars Short Stories: The League of Spies Sidhe-Devil

Sidhe-Devil Star Wars: Legacy of the Force: Fury

Star Wars: Legacy of the Force: Fury Starfighters of Adumar

Starfighters of Adumar Star Wars: X-Wing VI: Iron Fist

Star Wars: X-Wing VI: Iron Fist Star Wars - X-Wing - Iron Fist

Star Wars - X-Wing - Iron Fist Exile

Exile Star Wars: X-Wing V: Wraith Squadron

Star Wars: X-Wing V: Wraith Squadron Star Wars - X-Wing - Starfighters of Adumar

Star Wars - X-Wing - Starfighters of Adumar Rebel Stand: Enemy Lines II

Rebel Stand: Enemy Lines II Rebel Dream: Enemy Lines I

Rebel Dream: Enemy Lines I Outcast

Outcast Star Wars - X-Wing 07 - Solo Command

Star Wars - X-Wing 07 - Solo Command